~ Prof. Peter Erlinder

The encroachment of sulfide mining industries poses a grave threat to the waters and ecosystems in northern Minnesota. Mining wastes containing sulfates, methyl mercury, and sulfuric acid will turn the pristine environment into a biohazard zone for humans and wildlife alike.

In their quest to establish regional mining districts, extractive resource entities have employed an array of tactics to undermine resistance to resource colonialism. One tactic is the marginalization of treaty rights. Marginalizing tribal sovereignty is like the elephant in the living room that they don’t want to acknowledge or want people to see. It feeds on the misperception that tribes simply gave up their land in exchange for reservations.

Marginalization denies the fact that tribes retained the right to hunt, fish, and gather on off-reservation ceded land. And embedded within the treaties are environmental protections to sustain sustenance resources for tribal well-being – not only on-reservation, but off-reservation as well.

Indeed, treaties may very well be the endpoint in the effort to save our environment.

I

Comment Noted

“My friends, is it the truth? We don’t dispute it, but is it the truth, all that you have said – will it transpire?”

~ Nagonegwonabe (Leading Feather), Red Lake Ogimaa, speaking on the 1889 Agreement

In his speech before treaty negotiators, Nagonegwonabe alluded to the 1863 Treaty of Old Crossing, which the government failed to uphold. Yet his question was not exclusive to Red Lake. Other Anishinaabe leaders who signed treaties in the 1880s asked essentially the same question.

Over one-hundred and twenty years later, it’s a question that remains valid. Will the truth transpire today that our reserved treaty rights will protect our ceded lands against the growing danger of extractive resource colonies in northern Minnesota?

In the quest to establish extractive resource hegemony in Minnesota, mining entities, under the guise of corporate personhood, have relied on a pro-mining legislature to enact laws that favor mining interests at the cost of the environment. Previous laws to protect the environment have been weakened to the point in which current regulations have little value or meaning.

In the pursuit of establishing hegemony, extractive resource entities have, with seeming purpose, overlooked the role of treaty rights, in particular reserved treaty rights that emphasize the off-reservation rights to hunt, fish, and gather on tribal ceded lands and the protection of those sustenance resources.

One of the best examples of this marginalization of treaty rights is the comments of Essar Steel Minnesota, a taconite company that released its Draft Supplemental EIS in 2010 for their modification/expansion project. In the Public Comments Responses, the Leech Lake Anishinaabe Nation submitted their concerns regarding Essar’s expansion.

Comment 1: The Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe (Band) is providing comments on Essar Steel Minnesota DSEIS in part as official involvement in the permitting process. However, of greater consequence is the Band’s sovereign status and our obligation and ability to protect our people and our environment today and for generations to come. In addition, the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe has Treatment as an Affected Sovereign/State (TAS) status under Section 106 of the Clean Water Act to protect the health and well-being of the environment and its members by means of protecting wetlands and water resources

Response 1: Comment noted.

Comment 2: The Band is interested in and has been involved in the process of the Essar Steel Minnesota project as it has the potential to impact Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe members and resources both on the Reservation and within the Band’s 1855 Ceded Territory. The project is 28 miles from the Reservation boundary, well within the 50 mile TAS radius. Emissions from this project and the facilities around the Essar mining operation affects areas where Leech Lake Band members hunt, fish, gather, recreate, and live. The Leech Lake Reservation is a federally recognized Reservation located in north-central Minnesota encompassing 865,000 acres, serving 8,050 members, and 12,000 Reservation residents. The Reservation is characterized by an abundance of lakes and rivers (approximately 300,000 acres of surface waters), wetlands (163,000 acres), and forests (over 300,000 acres). The Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe retained and exercise their inherent right to hunt, fish, and gather for subsistence purposes in the 1855 Treaty with the United States government. Resources must be available and safe to utilize for the exercise of these rights. Protection of the Reservation’s environment and trust resources is crucial for the health and welfare of the Reservation population and the traditional, cultural and spiritual well-being of the Band.

Response 2: Comment noted.

Leech Lake also submitted an additional comment that specifically focused on the Clean Air Act. Essar’s response was - comment noted.

In their comments, Leech Lake cited protections under reserved treaty rights – i.e., “inherent right to hunt, fish, and gather for subsistence purposes,” under the 1855 treaty and ceded territory. In addition, Leech Lake referred to protections under the Clean Water Act (CWA) and to the Clean Air Act (CAA).

Essar’s failure to acknowledge treaty rights indicates they’ve chosen to ignore the treaty. Marginalizing treaty rights as simply “comment noted,” doesn’t resolve the issue for Essar, or other extractive resource industries for that matter.

II

Reserved Treaty Rights

Tribes negotiated treaties because they were at great risk of complete subjugation of their traditional land bases. In the case of the Anishinaabeg, the Ogimaag (leaders) were well aware that the cession of their lands could not be avoided. They negotiated to keep what they could. Indeed, the Anishinaabe word for reservation is ishkonigan, means “land that is left over.” However, the Ogimaag knew that ishkoniganan (reservations) would not provide the sustenance needed to provide for their people. Therefore, they retained their usufructuary rights – the rights to hunt, fish, and gather on their ceded lands. These reserved treaty rights were never granted; rather, they were written into the treaties in accordance with terms dictated by tribal leaders.

In U.S. v. Winyans (1905), the U.S. Supreme Court was clear that treaties were not a grant of rights, but a grant of right from tribes:

“The right to resort to the fishing places in controversy was a part of larger rights possessed by the Indians…New conditions came into existence, to which those rights had to be accommodated. Only a limitation of them, however, was necessary and intended, not a taking away. In other words, the treaty was not a grant of rights to the Indians, but a grant of right from them, – a reservation of those not granted. And the form of the instrument and its language was adapted to that purpose. ..There was an exclusive right of fishing reserved within certain boundaries. There was a right outside of those boundaries reserved 'in common with citizens of the territory.” (Italics mine)

Three years later, Winters, et. al. v. United States (1908), was heard by the Supreme Court. The Court affirmed the decree that enjoined companies from using the Fort Belknap tribe’s water source. The Winters Decision established reserved water rights in that self-sufficiency was dependent on tribal water resources and those resources, located off the reservation, were protected to maintain tribal well-being and lifeway.

The issue of reserved treaty rights was more specifically addressed in Tulee v. State of Washington (1942). In this case, heard by the State Supreme Court of Washington, state agencies were enforcing fishing fees on the Yakimas. As stated in the suit:

“The exclusive right of taking fish in all the streams, where running through or bordering said reservation, is further secured to said confederated tribes and bands of Indians, as also the right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed places, in common with citizens of the Territory…with the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries, and pasturing their horses and cattle upon open and unclaimed land.”

In 1974, reserved treaty rights and responsibilities were more firmly defined through U.S./ Quinault Tribes of Indians et al. v. State of Washington (also referred to as the Boldt Decision). The Boldt Decision held that the tribes had the right to fish, and this right included off-reservation fishing sites. The decision also set specific limits to the fish harvest – 50% to the tribes and 50% to non-Natives. Boldt didn’t provide exclusive environmental protections to the tribes. Rather, the protections were intended for both Natives and non-Natives. In other words, they each had a responsibility to protect natural resources and to work collaboratively to achieve those goals.

Although Winyans and these cases clearly established recognition of reserved treaty rights, those reserved rights have never been forthrightly recognized by states. Rather, reserved treaty rights have always had to be, and continue to be, litigated.

III

Anishinaabeg Reserved Treaty Rights in Minnesota

1837, 1854, and 1866 Ceded Lands

In Minnesota, reserved treaty rights became an issue in the mid-1980s. The Grand Portage Band sued the State of Minnesota in regard to usufructuary rights under the 1864 treaty. The Bois Forte and Fond du Lac Bands, who were signatories to the treaty, also joined the lawsuit. In 1986, the bands and the state negotiated a tribal/state agreement under which some off-reservation rights were limited in exchange for an annual payment from the state. However, this did not exclude all usufructuary rights.

In 1990, the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe began its suit against the State on Minnesota in regard to the 1837 and 1854 treaties. This would eventually culminate in the 1999 U.S. Supreme Court Decision that affirmed the usufructuary rights of the Mille Lacs Band.

One of the main points of contention was Article 5 of the 1837 treaty: “The privilege of hunting, fishing, and gathering the wild rice, upon the lands, the rivers and the lakes included in the territory ceded, is guarantied [sic] to the Indians, during the pleasure of the President of the United States.”

Although Taylor issued an executive order to terminate the 1837 usufructuary rights, the Court found the order invalid since Taylor lacked Congressional approval or Constitutional approval to do so.

The State also argued that the Mille Lacs Band had abrogated their usufructuary rights under the 1855 treaty. In Article 1, second sentence, the treaty states: “And the said Indians do further fully and entirely relinquish and convey to the United States, any and all right, title, and interest, of whatsoever nature the same may be, which they may now have in, and to any other lands in the Territory of Minnesota or elsewhere.”

The Court refuted this claim: “At the very least, the historical record refutes the State’s assertion that the 1855 Treaty “unambiguously” abrogated the 1837 hunting, fishing, and gathering privileges. Given this plausible ambiguity, we cannot agree with the State that the 1855 Treaty abrogated Chippewa usufructuary rights. We have held that Indian treaties are to be interpreted liberally in favor of the Indians, and that any ambiguities are to be resolved in their favor.”

1855 Ceded Land

Among the signatories of the 1855 treaty were the Anishinaabeg of the Sandy Lake, Leech Lake, White Earth, and Mille Lacs Nations. In the 1999 Supreme Court Decision, those rights were affirmed for the Mille Lacs Band in regard to the 1837 treaty and to Fond du Lac under the 1854 treaty (and also the Grand Portage and Bois Forte Bands who were signatories to the 1854 treaty). The 1855 treaty was integral to the Court’s decision. As cited:

“The entire 1855 Treaty, in fact, is devoid of any language expressly mentioning–much less abrogating–usufructuary rights….The 1855 Treaty was designed primarily to transfer Chippewa land to the United States, not to terminate Chippewa usufructuary rights.”

However, the decision did not affirm the usufructuary rights of 1855 signatory Bands because they were not parties to the lawsuit. Thus, although their rights were recognized, those rights were not litigated by the signatory Bands.

In 2010, treaty activists staged a rally on the shore of Lake Bemidji, on the day before the fishing opener, to shed light on the issue of usufructuary rights in the 1855 ceded land. A White Earth tribal member set gill nets. The Minnesota DNR cut and confiscated his nets. The tribal member was not charged with illegal netting that carries a one-year jail sentence. In addition, his boat and motor were not confiscated. Notably, the member was not penalized under the full extent of the law because of the state’s desire to avoid media focus on the issue of the 1855 treaty.

The rally led to the formation of the 1855 Treaty Commission. The Commission is composed of two members from White Earth, two from Leech Lake, two from Sandy Lake, and two from East Lake. East Lake was formerly part of the Sandy Lake Nation and signatory to the 1855 treaty. The commission was established to develop conservation rules to regulate hunting and fishing on their respective reservations, and regulate usufructuary rights off-reservation. Although the commission has had informal meetings with the DNR, the DNR continues to enforce game and fish laws.

The 1863 and 1889 Ceded Land

In 1863, the Red Lake Band entered into a treaty (and an amended treaty in 1864) in which they ceded the western portion of their lands. The pretext for the 1863 treaty was for right of way through Red Lake and Pembina homelands, but when the negotiations ended, the government gained 11 million acres of prime farmland and forested areas.

Although usufructuary rights were not written into the treaty, it was clearly understood that the Red Lake Band retained those rights.

Governor Alexander Ramsey, the chief government negotiator, assured that Red Lake would maintain its usufructuary rights:

Governor Ramsey: “You lose nothing by it [the Treaty]. You can still hunt and fish throughout your country as usual…they would have the privilege, for many years, at least, of hunting over these lands as before.”

Treaty making ended in 1871. In 1889, under the auspices of An Act for the Relief and Civilization of the Chippewa Indians in the State of Minnesota, the government sent negotiators to Red Lake to obtain land that would be ceded via the Allotment Act.

After seven days of negotiations, the Red Lake Band relented and ceded 2,905,000 acres of land but it was predicated on the condition that they would retain the whole of the Lake (Upper and Lower Red Lake). Indeed, the 1889 Commission Report documents Red Lake’s repeated stipulation to retain the Lake. However, once the negotiators arrived in Washington, the survey line was moved and an eastern portion of the Lake was ceded. (This remains a point of contention today.)

In 1902, the government created An Amendment to the Act of January 14, 1889. This was the government’s effort, once again, to subjugate Red Lake land located on the western perimeters of the reservation line. This area was known as the 11 Western Townships and included 256,152 acres. Under the 1902 Agreement, the Red Lake Band received $1.25 million for the land.

According to the Minutes of Councils, Red Lake leaders brought up past issues in regard to the 1863 treaty and the 1889 agreement. Peter Graves, who would later organize the General Council of the Red Lake Band, spoke about the grievances.

Regarding the 1889 Agreement:

“And there is lots of pine left standing that has not been cut on the lands we ceded to the United States. And we were given to understand that we had the use of any ceded land that was not occupied by settlers, to be used as our own. And furthermore we reserved the privilege of using that as our hunting grounds as in former years.”

III

The Implications of Minnesota Reserved Treaty Rights and Extractive Resource Colonies

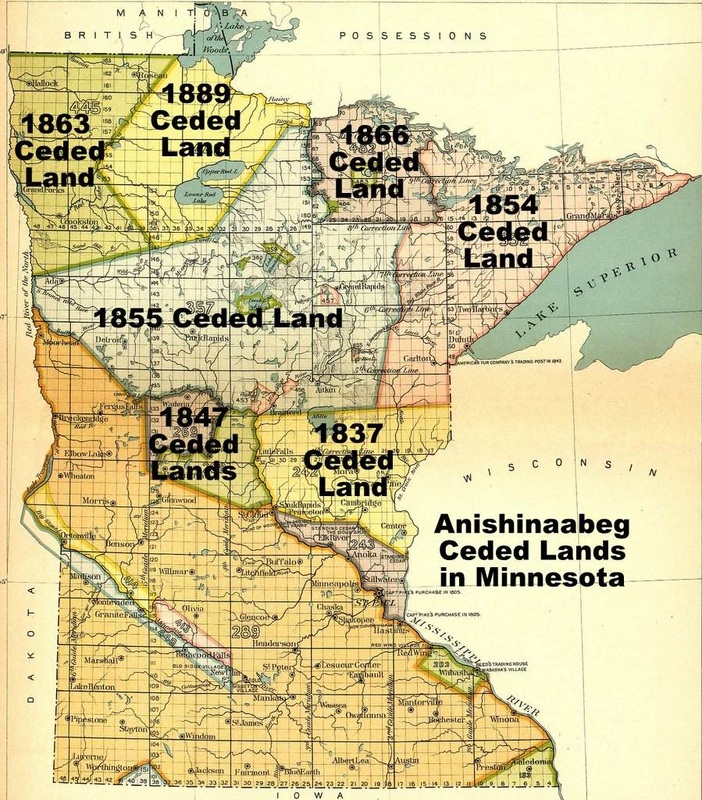

The foregoing section - Anishinaabeg Reserved Treaty Rights in Minnesota – presents a brief overview of reserved treaty rights in the ceded lands of the Anishinaabeg. Those rights cover nearly half of the state of Minnesota. The1837 and 1854 ceded lands have been affirmed through court decisions. The 1855 and 1863/1889 ceded lands have yet to be litigated. However, as the treaties and documents show, the indigenous peoples of those lands clearly retained their usufructuary rights.

In a guidebook written for Minnesota legislators, “Indians, Indian Tribes, and State Government,” the definition of Minnesota Indian Country recognizes off-reservation rights:

“Tribal territory, or Indian Country, is a crucial concept of Indian law. Under federal law, tribal territory defines the jurisdiction of tribes, the federal government, and state government. It is generally within these areas that tribal sovereignty applies and state power is limited. Certain tribal powers – for example, the ability to take game and fish, and harvest native crops ‘off-reservation’ – may apply outside the area of Indian country under specific treaties or statutes. “

As noted earlier, federal Indian law provides precedents that not only clarify usufructuary rights, but also the protections that are provided under those rights.

In the far-reaching Winyans decision, on- and off-reservation rights had to be recognized to “give effect to the treaty.” The Winters case affirmed that protections – in this case, a river - included boundaries that went beyond reservation lines:

“It is alleged with detail that all of the waters of the river are necessary for all those purposes and the purposes for which the reservation was created, and that in furthering and advancing the civilization and improvement of the Indians, and to encourage habits of industry and thrift among them, it is essential and necessary that all of the waters of the river flow down the channel uninterruptedly and undiminished in quantity and undeteriorated in quality.”

Both the Winyans and Winters decisions underscore the importance of protection, protection retained through treaties, of off-reservation resources for tribes to maintain their subsistence well-being.

In Minnesota, marginalizing treaty rights ignores a geographical area that has been successful in litigating those rights as evidenced by the 1999 Supreme Court Decision and the 1983 Voight Decision in Wisconsin. Dependence on legislation that diminishes environmental protections doesn’t resolve the situation since those laws not only violate tribal sovereignty but also violate the public trust. The issue of reserved treaty rights is a legal obstacle that extractive resource entities have yet to face.

Equally important is the role of tribal governments. In asserting our treaty rights, tribal councils need to rethink the structure of majoritarian rule and readapt to the thinking of the original signatories of the treaties. When our leaders signed treaties, they were not simply retaining sustenance rights. They were also retaining our reciprocal affiliation with the environment. The spirits, other-than-human persons, birds, animals, plants, and the waters were all part of our reciprocal affiliation. Although that interconnectedness wasn’t written into the treaties, it was implied in treaty negotiations.

For example, in the negotiations for the Red Lake and Pembina treaty in 1863, Little Rock alluded to the reciprocal relationship between humans and nature: “My friend, when we take anything that has been left upon the ground, even though it be of small value, we feel bad. We are afraid to look the owner in the face until we can restore it…Here, on this track, is where my grandfather was placed – the one who made the soil…At the time my grandfather was put on the soil there were two creatures of every kind, of different sexes, that were put along with him, which he was to get his food and clothing.”

In referencing “grandfather,” Little Rock was addressing an other-than-human person, a spiritual entity. This tribal holism was unrecognized by treaty negotiators because the western mindset separated nature from society. With the imposed establishment of “modern” tribal governments under the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) in 1934, traditional council structures were disenfranchised. The progressive politics of IRA governments became separated from tribal holism.

With the dire threat of ecocide of tribal lands from extractive resource industries, tribal councils need to not only assert treaty rights but also need to integrate Traditional Ecological Knowledge to emphasize the interconnectedness that our forebears sought to retain in our reserved treaty rights.

It is also pertinent that the people whose lives will be affected have a role in the decision making process. As stakeholders, their sustenance is dependent on a clean and healthy environment not only for the present generation but for subsequent generations as well. All too often, tribal councils make decisions on behalf of their people without consulting the people. In the issue of mining, the people need to be informed about the issues and be a part of the decision making process. Decisions on mining should not be exclusive to tribal councils. Through referendums the people can make their voice heard.

As exploration maps have shown, the grand scheme of extractive resource industries is to establish a hegemony that extends from the shores of Anishinaabe-gichigami (Lake Superior) into the interior of northern and central Minnesota. They have already found what they were looking for – copper, nickel, gold, silver, titanium. Under current legislation, the permit process has been streamlined. To their way of thinking, it is only a matter of time before they begin drilling and extracting metals from the earth. These extractive resource colonies are financed by powerful foreign mining conglomerates like Rio Tinto, Glencore, and Antofagasta. These conglomerates have violated the human rights of indigenous peoples in South America, Africa, and Indonesia, and have marginalized the land rights of those peoples with the help of governments. But marginalizing indigenous land rights in the United States presents specific obstacles because of tribal sovereignty inherent in treaties. Therefore, assertion of treaty rights, and federal Indian law, is crucial in undermining the attempt of extractive resource industries to establish hegemony in the Anishinaabe homelands, including the ceded lands. But it needs to be done in a timely manner. And that time is now.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed